Giving a speech was a woman identified as Duwaraka, the daughter of Tamil Tiger terrorist head Velupillai Prabhakaran.

The issue stemmed from the fact that Duwaraka passed away almost ten years prior, in an airstrike that occurred in 2009 during the final stages of the civil war in Sri Lanka. The body of the 23-year-old was never located.

And here she was, apparently a middle-aged woman, urging Tamil people everywhere to continue the political fight for their independence.

After extensively examining the film and identifying several technical issues, Mr. Chinnadurai, a fact-checker from the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, quickly concluded that the figure was created using artificial intelligence (AI).

Mr. Chinnadurai saw the potential issues right away: “This is an emotive issue in the state [Tamil Nadu], and with elections coming up, the misinformation could spread quickly.”

It is hard to ignore the abundance of AI-generated content that is being produced as India prepares for elections. This includes automated calls to voters voiced by candidates, personalized audio messages in a variety of Indian languages, and campaign videos.

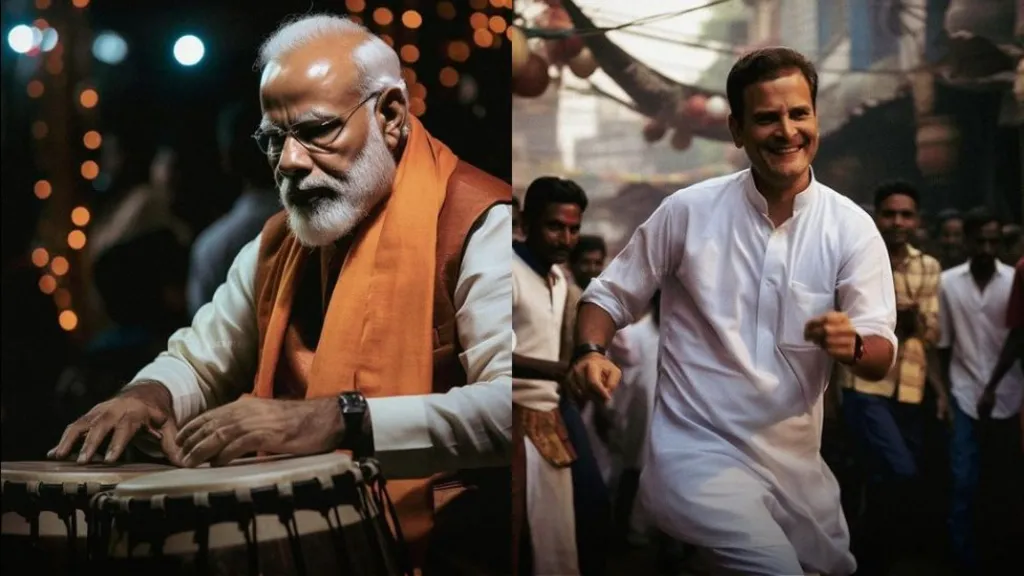

Using AI techniques, content artists such as Shahid Sheikh have even enjoyed creating avatars of Indian politicians that we haven’t seen before, such as ones that dance, perform music, and wear athleisure.

However, experts are concerned about the ramifications of more sophisticated technologies for disguising bogus news as real.

There have always been rumors during political campaigns. However, in the era of social media, it can quickly spread,” remarks SY Qureshi, the nation’s previous chief electoral commissioner.

Political parties in India are hardly the first in the world to capitalize on the latest advancements in artificial intelligence. It made it possible for imprisoned politician Imran Khan to speak at a rally in Pakistan, just across the border.

Additionally, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India has already efficiently used emerging technologies to further his campaign. He spoke to an audience in Hindi, which was instantly translated into Tamil using the government-developed artificial intelligence program Bhashini.

However, it can also be utilized to change messages and words.

Two widely shared videos from last month had Bollywood actors Aamir Khan and Ranveer Singh endorsing the opposition Congress party. Both reported to the police that these were deepfakes that were created without their permission.

Then, on April 29, Prime Minister Modi expressed alarm over the use of AI to stifle remarks made by him and other prominent members of the ruling party.

In relation to a manipulated video of Home Minister Amit Shah, police detained two persons the next day: one from the opposition Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) and the other from the Congress party.

Opposition politicians in the nation have also leveled similar charges against Mr. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Experts claim that the issue is that, despite the arrests, there isn’t a thorough regulation in place.

It implies, in the words of data and security expert Srinivas Kodali, “if you’re caught doing something wrong, then there might be a slap on your wrist at best”.

Creators told the BBC that in the lack of regulations, their decision on what kind of work to do or not do is based solely on personal principles.

According to information obtained by the BBC, politicians requested the use of pornographic images and the alteration of rivals’ audio and video content in order to harm their reputation.

“I was once asked to make an original look like a deepfake because the original video, if shared widely, would make the politician look bad,” says Divyendra Singh Jadoun.

“So his team wanted me to create a deepfake that they could pass off as the original.”

Mr. Jadoun, the creator of The Indian Deepfaker (TID), insisted on including disclaimers on everything he produced to make it obvious that it was not real. TID developed tools to assist people in using open source AI technologies to create campaign material for Indian politicians.

However, control is still difficult.

Getty Image

Politician Imran Khan, who is incarcerated in Pakistan, spoke during a rally using AI.

Working for a marketing business in the eastern state of West Bengal, Mr. Sheikh has observed politicians and political pages sharing his work on social media without granting him permission or credit.

“One politician used an image I created of Mr Modi without context and without mentioning it was created using AI,” he claims.

Furthermore, anyone can now make a deepfake because it is so simple to do so.

“What used to take us seven or eight days to create can now be done in three minutes,” Jadoun says. “You just need to have a computer.”

In fact, the BBC had the opportunity to observe firsthand how simple it is to set up a fictitious phone conversation between two individuals—in this case, myself and former US President Donald Trump.

India had originally stated that it was not considering enacting an AI law, despite the hazards. However, it was triggered in March following a controversy around Google’s Gemini chatbot’s response to a question posed, “Is Modi a fascist?”

The nation’s junior minister of information technology, Rajeev Chandrasekhar, said that it had broken several IT-related laws.

Since then, before releasing “unreliable” or “under-tested” generative AI models or tools to the public, the Indian government has requested tech companies to obtain its express consent. Furthermore, responses that “threaten the integrity of the electoral process” should be avoided, according to this warning.

However, fact-checkers claim that this is insufficient and that it is difficult to keep up with the debunking of such content, especially during election seasons when disinformation is at its height.

“Data moves at a hundred kilometers per hour,” claims Mr. Chinnadurai, the head of a media monitoring organization in Tamil Nadu. “The debunked information we disseminate will go at 20km per hour.”

According to Mr. Kodali, these fakes are even getting into the mainstream media. The “election commission is publicly silent on AI” in spite of this.

“At large, there are no rules,” Mr. Kodali asserts. “They’re letting the tech industry self-regulate instead of coming up with actual regulations.”

Experts claim that no infallible answer is in sight.

“But [for now] if action is taken against people forwarding fakes, it might scare others against sharing unverified information,” says Qureshi.

For more you can further explore our Global section.